Community Conversations with Kendra Lowery

As the associate dean for equity and engagement in Teachers College at Ball State University, I have the privilege to converse with people across the community who uplift education in a variety of ways. I am pleased to highlight their stories.

Neil Kring

On a late October day, I stopped by Neil Kring’s house to talk with him about his community-engaged work on the southside of Muncie. He told me that I could meet him at his garage which “backs up to the back” of Avondale United Methodist Church. Indeed, his garage literally backs up to the church with no more than 25 feet of space between the two properties! Neil was outside when I pulled up to park and I was instantly captivated by his surroundings. It is a glorious garage. It is full of bicycles, tools, and lights that are hung throughout. His backyard was full of life, including peppers (lots of peppers!), pretty flowers that were hanging on to enjoy the last days of the season, and a fire pit surrounded by chairs. The parking lot, which is owned by the church, is nicely paved with a basketball hoop that neighborhood children frequently use. It was one of the last mild days of the season, so we were able to talk outside in front of the garage where Neil has a bistro table and chairs set up in front of his fenced-in yard.

Those familiar with the southside know that Neil lives across from the brownfield left by the demolition of the General Motors manual transmission plant. The plant, known as “Chevrolet Muncie,” “Muncie Chevrolet,” or “the Chevy plant,” closed in 2006 and was fully demolished by the end of 2008.

Ball State University Archives and Special Collections

Much has been written and discussed regarding the significant loss to Muncie and the southside community after the GM plant, which breathed a lot of economic life into the community, closed. One of the best things about my job is that as I engage with communities and schools, I search for what has sustained, community strengths, and how people are surviving and thriving even in the face of a legacy of economic divestment and resulting social, political, health, and educational challenges in their communities. I get to meet people like Neil Kring.

Neil was a pastor of a campus church at Ball State for over twenty years. He mostly worked with college students and facilitated a student-led church. Some of the students got involved in the meal ministry at Avondale United Methodist Church which serves meals to the community every Thursday. Through his work in the meal ministry, Neil developed relationships and learned more about the community and the challenges people faced, particularly with substance abuse, poverty, and a lack of community resources to adequately address these challenges. He was moved to increase his involvement. In 2019, his family moved into his current home in the neighborhood. He explained, “we moved without any specific purpose because we’d gotten to know people. If we’re together, maybe we could work on some things together.” Neil was drawn to what might happen because of getting to know and living among community members – in short, the possibilities that emerge from equitable relationships.

Shortly after he moved in, Neil noticed there were several young males, some black and some white, hanging around the neighborhood with nothing to do. They would sometimes get into mischief like hanging out on private lawns or annoying the neighbors. Knowing that kids did not want to stay in the house all day, he wondered, “What sorts of engagement can we do with kids on the street?”

One incident became a catalyst for the creation of the bike repair shop. A group of fourth and fifth grade boys threw a rock through the window of an abandoned house near Neil’s property which was owned by the church. In a show of restorative discipline, the pastor of the church, the police, and the boys’ mothers agreed that to address and restore their error, the kids would go to Avondale’s Vacation Bible School and help to repair the window. The boys followed through on their agreement. When they showed up for Vacation Bible School the following week, they were disappointed to learn it was over. Neil could see they wanted more structured activities.

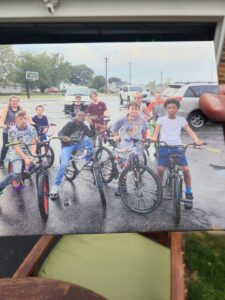

Rather than wondering about possibilities too far out of his reach and thinking about the obstacles he faced in creating a structured activity, Neil started with what he had – a garage and a skill set with bikes. Neil knows how to fix bikes because his dad was “into bikes, so he always worked on them.” He applied for and received a grant to start a bike repair shop in his garage. The shop opened in 2019. Neighborhood kids could get a bike if they worked to fix it. In order for kids to get a bike, Neil said, “You have to have a tool in your hand.” Boys and girls participate in the program. In fact, Neil recalled, “Girls from Southside Middle were some of the best mechanics.”

Neil Kring understands what it means to be a community advocate. He is not a savior or a fixer; he is a collaborator. He lives in and loves his community and asks, “Is there something we could do together?” During the height of COVID, he met with neighbors to think about how to develop a strategy to reduce drug overdoses. He took a community organizing course through Harvard University. In 2021, the group advocated for a 24-hour crisis center to be built on the southside. Neighbors showed up for city council meetings and told their stories. Their efforts paid off. A crisis center is set to be finished in their community in the spring of 2024.

Neil is quick to point out that he doesn’t work alone. He was recently trained through the Credible Messenger Approach which trains community members, some who are formerly incarcerated, how to engage with kids who are likely to engage in the criminal justice system. Neil and 25 community members, most of whom were from the historically Black Industry neighborhood, collaborated with judges, the 8twelve Coalition, and other community members.

It’s appropriate that Neil operates a bike repair shop because, as the saying goes, his wheels are always spinning. He has a dream of taking the bike shop into schools as an alternative learning opportunity or running an after-school bike club. Another item on his agenda is to collaboratively address the question, “How do we get kids to engage with leaders about education?”

Regarding his approach to community organizing, Neil asserted, “We’re not going to do things for people; we’re gonna do things with them.”

Neil loves his neighborhood. He explained, “It’s real easy to make connections with people here. Not as many people have air conditioners and people hang out in their driveways.” He’s always learning. I asked him about his massive garden. He explained he had no prior gardening skills but learned during the height of the COVID period because “I couldn’t sit in the house.” He now grows flowers, asparagus, and lots of really hot ghost peppers.

As if to accentuate Neil’s community involvement, while we ended our conversation, a group of three neighborhood boys rode their bikes across the parking lot, waved hello to Neil and gathered around the basketball hoop. Neil asked one of the boys if he still planned to perform at an evening performance, nodded to the driver, and stayed around to chat with the boys as I drove away.